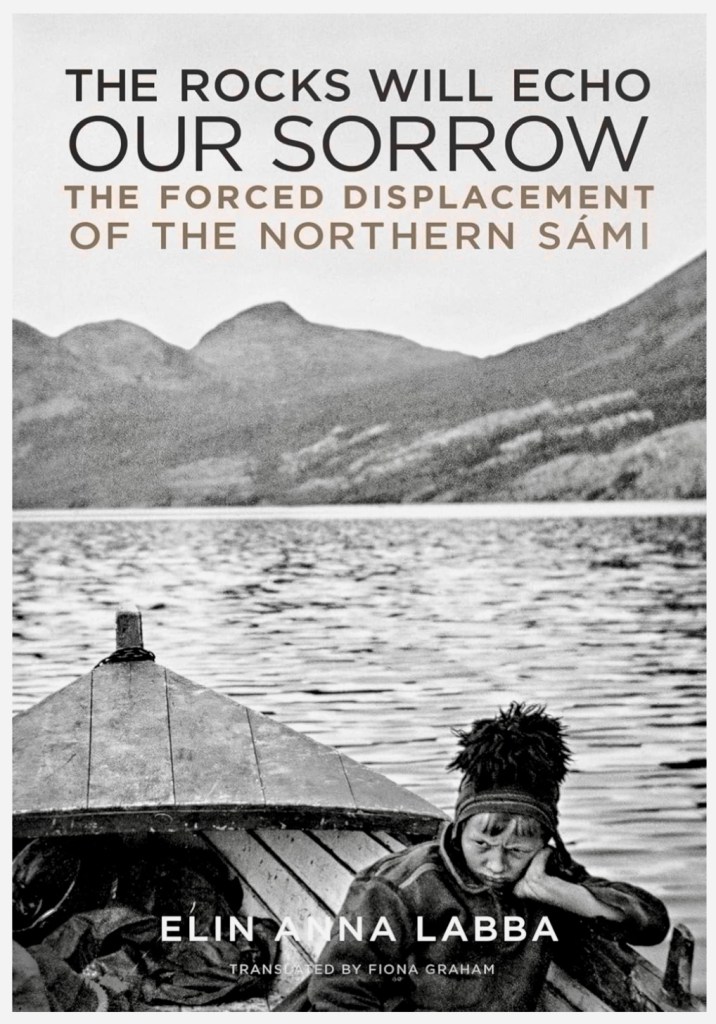

In September my review (below) was published on the pages of European Literature Network, run by Rosie Goldsmith, Anna Blasiak and West Camel. It’s always an honour and a plasure to contribute to this exciting and super interesting project / venture. I’d encourage you to read Elin Anna Labba’s book and also other works reviewed and recommended by European Literature Network’s team.

‘The elders spoke of how they used to greet the land when they came here, the mountains, the dwelling places, and the paths, but I dare not. Just where do I belong? What is my home? I have discussed this with other grandchildren of forcibly displaced people.’

Before I focus on The Rocks Will Echo Our Sorrow, allow me to begin with mentioning a different novel: Petra Rautiainen’s Land of Snow and Ashes (translated from the Finnish by David Hackston), which is set after World War Two and affected me profoundly. One strand of this novel deals with Finland’s fairly recent traumatic history of forcing Sámi people to abandon their heritage, culture and identity to become ‘pure’ Finnish citizens.

Elin Anna Labba’s deeply personal and somehow universal The Rocks Will Echo Our Sorrow: The Forced Displacement of the Northern Sámi therefore stopped me in my tracks. It is a truly heart-wrenching examination of the new rules that were imposed in the early twentieth century on the indigenous people who had lived for centuries in northern Scandinavia. Their forced removal remains a deeply painful memory. Shame, injustice and hurt prevail in this book, alongside lyrical images of longing, and of the irreplaceable human costs borne in the harsh but ultimately stunning natural world of the region.

The author travels to this lost homeland of her ancestors, aiming to reclaim their place in the history of both Norway and Sweden. Labba, a Sámi journalist and previously editor-in-chief of the magazine Nuorat, asks herself: ‘Do I have the right to mourn for a place that has never been mine?’, and is of course aware that ‘boundaries have always existed, but they used to follow the edges of marshes, valleys, forests, and mountain ranges’.

Nature and its seasons, the environment and tradition, had dictated the way people lived, organised their work and travel in winter and summer, how they grazed their reindeer in specific areas and drove them across the straits between the islands and the mainland. They had roots, connections, customs, and different methods of grazing the strong animals, all essential for their existence. The lives of forest Sámi and mountain Sámi were shaped across the generations by the weather. And there were always real emotional and physical ties to places even if they moved between them: ‘We carry our homes in our hearts.’

On 5 February 1919, the reindeer-grazing convention that sparked the forced displacement of the Sámi was signed by the foreign ministers of Sweden and Norway. Soon after, the era of ‘racial biology’ research started in Sweden. The Lapp Authority then followed newly established laws on the reduction of reindeer numbers and decided which of the Sámi could stay on their land and who must move to a different area. The displacements ensued. The legislation was unclear to the ordinary Sámi people, and therefore the appeals they made failed to protect their families. This meant women and children were the most vulnerable members of the community. ‘Family ties are the most precious thing anyone can have, apart from reindeer’ and without them ‘a man who’s left his lands no longer has a home. He no longer has his feet on the ground’.

‘For many, recounting the tale is a way to heal’ and so The Rocks Will Echo Our Sorrow contains fragments of letters, conversations and poems, in excellent translation from Swedish by Fiona Graham, as well as old photographs showing difficult yet beautiful living conditions, and the nature of the Sámi existence: ‘You bear your hurt alone, for breaking down won’t make your daily life any easier. This philosophy of life revolves around the word birget – surviving and coping. Each year the reindeer must survive the winter: that is what matters, not people’s feelings.’ Fiona Graham translated also 1947: When Now Begins by Elisabeth Åsbrink, another book that affected me profoundly, from human, political and historical perspectives, and has been on my mind for the last two years.

Choosing and being in the culture of joiking, the goahti (tent) protecting them ‘against the wind, the darkness, and everything that can’t be seen’, against rain, snow and sun, and living according to tradition, should always have been the Sámi’s decision to make.