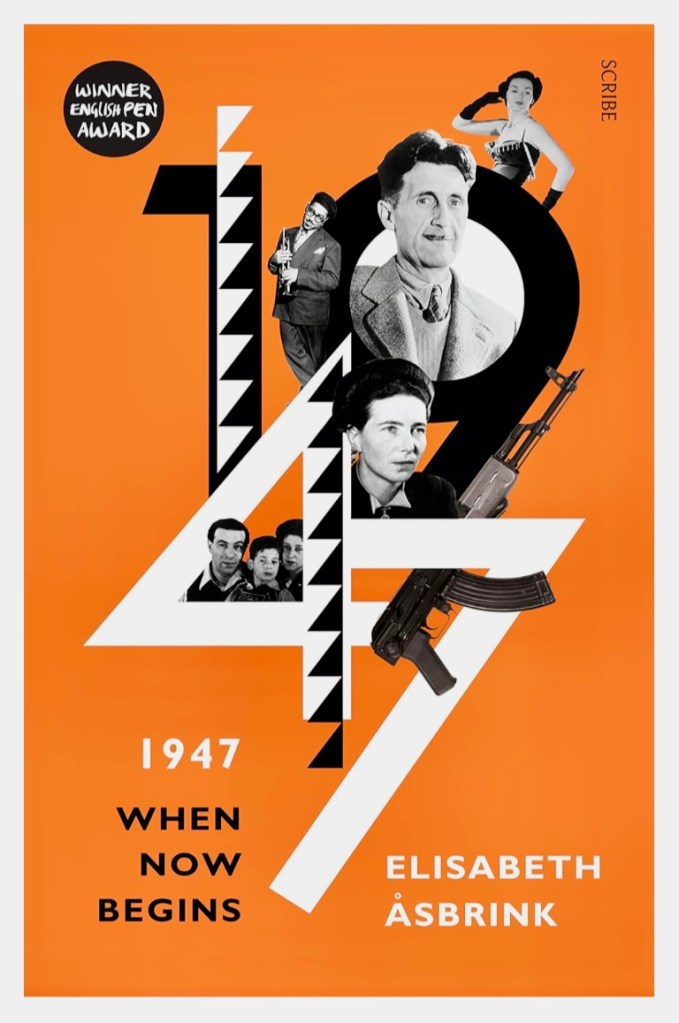

My first ever review for European Literature Network – 1947: When Now Begins by Elisabeth Åsbrink was published eight years ago. I’m feeling a touch nostalgic as I look through old reviews but I must also admit that Elisabeth Åsbrink‘s book has been on my mind for the last two years. Hence I would like to recommend it again. The world is changing rapidly and we must learn from the past – to do good.

In 1947, everything is changing. The world is set to become a very different place …

Christian Dior is designing his fabulous, sumptuous New Look dresses. Thelonius Monk is playing his ground-breaking jazz compositions and Billie Holliday is singing the blues. Grace Hopper, appointed as a mathematician in the US Navy, finds an actual computer bug: a moth stuck in a massive mainframe. Simone de Beauvoir longs for her American lover and writes The Second Sex, later hailed as feminist bible. Eric Arthur Blair, better known as George Orwell, is coughing his guts out as he works on 1984 on the Scottish island of Jura.

On the other side of the still invisible East – West border, Mikhail Kalashnikov finally gets the go-ahead to mass produce his deadly invention: a gas-operated machine gun. The Cold War map is reduced to black and white … nuances of grey: non-existent. British and American powers decide the fate of thousands of Jews and fight against communist influence. The Soviet Union hardens its ideology.

While the world tries to heal itself and for the most part cries ‘never again, never again’, the Nuremberg Trials are in full swing and finally there is a chance that a new crime of genocide will be recognised. Other opinions and thoughts allow the continuing flight of old Nazis to Argentina, thanks to their new sympathisers, who often gather in the Swedish town of Malmö, and spread the written Fascist credo like fire. Anxiety, cynicism, cold legal calculations, power games and deeply-rooted convictions provoke the creation of the CIA and underlie the origins of the Muslim Brotherhood and ISIS, based on Hassan Al-Banna’s ideology. The UN Committee has only four months to decide future of Palestine and in these tumultuous times must consider diametrically conflicting wishes and demands.

Amid the post war chaos and pain, amongst thousands of refugees, liberated prisoners and emaciated Jews, a ten-year-old Hungarian boy, Joszef, once called György, is in Ansbach in southern Germany, in the American zone. In a camp for children whose parents have been killed by Nazis, he needs to decide whether to travel to Palestine and start a new ‘Zionist’ life, or to return to Budapest, the city that was his home as well as the source of his persecution. His is also the personal story of the author: Joszef will eventually escape to Sweden where his daughter Elisabeth will be born.

The story moves through a devastated Europe, to the mighty US, which is launching the Marshall Plan, to a fragile Middle East, a torn-apart Indian subcontinent with millions of hurting Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs; it carries us seamlessly along. It’s a fascinating piece of non-fiction that reads like a vivid novel: the evolution of the world on a huge scale reveals small fissures through which we observe tiny moments in private lives.

Swedish author and journalist Elisabeth Åsbrink has written four books which have, between them, won the August Prize, the Danish-Swedish Cultural Fund Prize, and Poland’s Kapuscinski Prize. 1947: When Now Begins is her first book to appear in English, superbly translated by Fiona Graham, a winner of the English Pen Award. Åsbrink has created an exceptional and gripping chronicle of this one momentous post-Second World War year; it combines major events with small, individual histories of the people affected by what had happened only a few years previously, and what would continue to affect future generations. Åsbrink uses both snapshots and longer musings to ask important questions; yet she keeps her own emotions in check, barely allowing them to surface in the sea of pain, despair, unspeakable crimes and the occasional hope. She admits to attempting to define herself and her own authenticity through her detailed survey of the events of 1947: Grief over violence, shame over violence, grief over fame. In this 70th anniversary year, the book is in no way just a historical record: instead its themes are contemporary, valid, and urgent.

1947: When Now Begins is an extraordinary book, based on an incredible amount of research, presented in a very sober, sensitive way. It invites us to go in search of even more information. A highly recommended must-read.