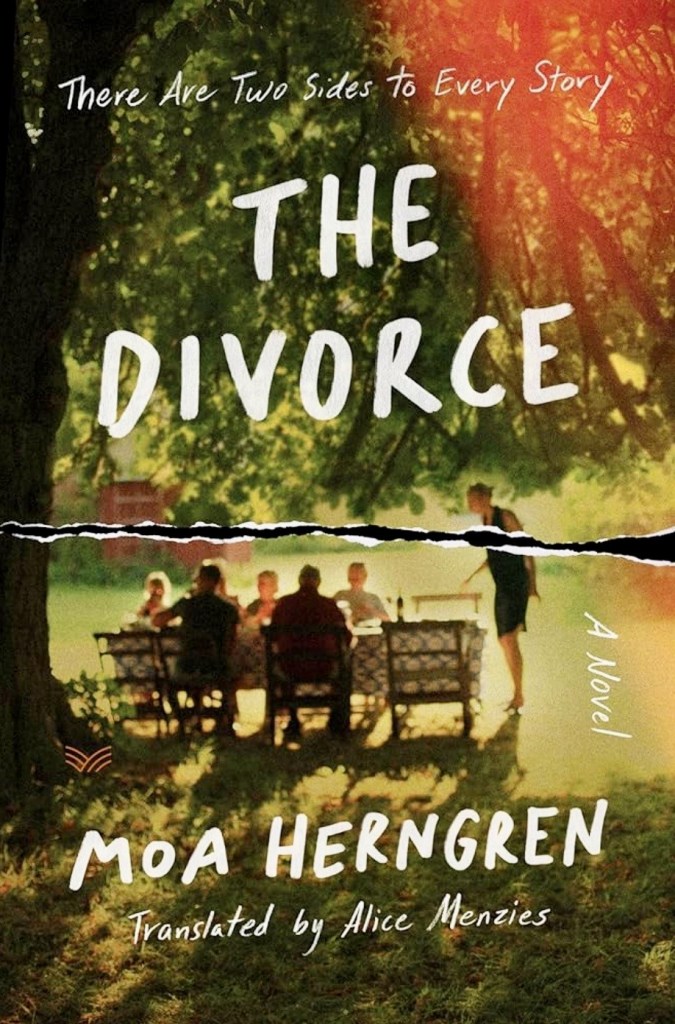

Nordic Noir it isn’t but let me tell you: the post-mortem examination carried out in The Divorce makes for the gripping, emotional and sometimes uncomfortable reading, just like the best examples of Swedish crime fiction. However, in this case the detailed ‘autopsy’ focuses on a relationship, dead or very close to death, while digging deep into all possible causes as why this particular marriage has not survived. Because it should have, yes?

The process is painful, difficult and – familiar. I’m sure it has happened to many couples at different stages of their lives, for all possible reasons: emotions, boredom, age, dissatisfaction, new job, new company, old habits etc. However, what is so powerfully done here is the brilliantly observed clash between the whole picture of supposedly happy marriage and of what might be lurking underneath the surface of predictable daily routines. The Scandinavian dream that wasn’t lovely nature, clean lines and warm fluffiness.

Seemingly content pair Bea and Niklas have been together for more than thirty years, and with their two teenage twin daughters they live a comfortable life in Stockholm. Their fairly calm existence is punctuated by ordinary family events, seasons of the year, cosy winter celebrations and summers on the island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea. Sounds pretty idyllic. Niklas’ parents have a house there, and spending holidays with other members of his family became one of the life’s anchors for Bea. One evening following a trivial argument, nota bene related to the annual summer trip, Niklas leaves home to calm down. He doesn’t return. He doesn’t want to communicate. Eventually he realises that he no longer wants to be married to Bea who has absolutely no idea as why this is happening. He still doesn’t want to talk while she wants and explanations.

Moa Herngren disseminates emotions, words, actions and expectations, and explores the unravelling of a marriage from two points of view. First we witness Bea’s shock and panic as the fundaments of her entire life collapse. Convinced that everything she has ever done is for the sake of her family, she struggles to understand her soon to be ex-husband. Niklas, on the other hand, feels that finally he has reached the point of acknowledging his needs, both private and professional. He also admits some feelings for their acquaintance. Friends and family members close to the couple take sides, keep away or offer advice in the situation. Decisions are raw and reckless. You know how it is. Daughters try to find own ways of coping with the revelations that their mother’s perfectly designed kitchen cannot compare with their father’s urge for a symbolic tattoo. Did they even notice that?

I’ve read this novel titled Rozwód in Polish, translated from Swedish by Wojciech Łygaś and I really couldn’t put it down. I believe the English version by Alice Menzies is equally excellent. Alice Menzies’ translations include work by Jonas Hassen Khemiri, Fredrik Backman, Tove Alsterdal and Jens Liljestrand.

Moa Herngren is a journalist, former editor-in-chief of Elle magazine and a highly sought-after manuscript writer. She is also the co-creator and writer on Netflix hit-show Bonus Family / Bonusfamiljen which is comedy and drama in equal parts, and deals with complexities of relationships in modern family life in Sweden. Bonus Family follows a new couple Lisa and Patrik, their children from previous marriages, and ex-spouses. It’s real, funny, serious and very enjoyable. After watching season one I feel that I need a good walk and maybe a cup of hot chocolate as a break between the episodes as the writing and acting in the series are fantastic; emotionally charged, full of big and small acts of human behaviour, longing for love and comfort.

Fans of Swedish TV might be familiar with Herngren’s earlier work: Black Lake/ Svartsjön, its first season shown on BBC Four in UK in 2017. The story was about a group of young friends visiting an abandoned ski resort in northern Sweden, where strange noises from the basement were just the start of a series of horrifying events. Part thriller / part horror, and not so typical Nordic Noir, yet it seems as though all my reading and viewing roads lead to this genre.