The snow is gone, sun is shining and birds are singing and world seems happy and relaxed as we stand in a long queue outside Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AS, one of the largest Norwegian publishing houses. It was founded in 1925 after buying rights to publications from the Danish company of the same name. However, right now nobody thinks of its illustrious history. The aim is to get inside the beautiful building in central Oslo and find a good seat to enjoy crime. International crime fiction in fact as the new Krimfestivalen is just about to begin. Since the free festival was first held in 2012, it has been a huge success, and now it is considered as one of the world’s leading crime festivals. Over three days fifty writers from Norway and abroad will share some of their secrets, writing tips and opinions in three locations; here at Gyldendal and two other publishers: Cappelen Damm and Aschehoug. The last or so decade has been a golden age for NordicNoir crime fiction. The festival organisers are keen to celebrate this phenomenon and keep Nordic crime fiction within the international perspective, and we – the fans – know how intriguing and fascinating various books in this genre are. We don’t seem to get enough of them, and luckily – the authors keep writing.

Lubna Jaffrey, Minister of Culture and Equality, and Ingeborg Volan, the publishing director at Gyldendal Litteratur, welcomed the crowd of readers and writers.

The festival began with the conversation between the journalist Hilde Sandvik and the shining global star Jo Nesbø who discussed various American themes that have influenced both his life and his latest thriller. The English translation by Robert Ferguson is due to be published in August 2025. Minnesota or Wolf Hour, set in the American Midwest in 2016, brings a powerful mix of unexpected twists, dark secrets and personal and political tension. Here’s the blurb: ‘When a small-time crook is shot down in the street, all signs point to a lone wolf, a sniper who has seemingly vanished into thin air. Down-and-out detective Bob Oz is sitting in a dive bar in Minneapolis when he gets a call: there’s been another murder, and they don’t think it will be the last. As the body count grows, Oz suspects that something more sinister is at play. And the closer he gets the more disturbed he becomes. Because the serial killer reminds him of someone: himself’.’

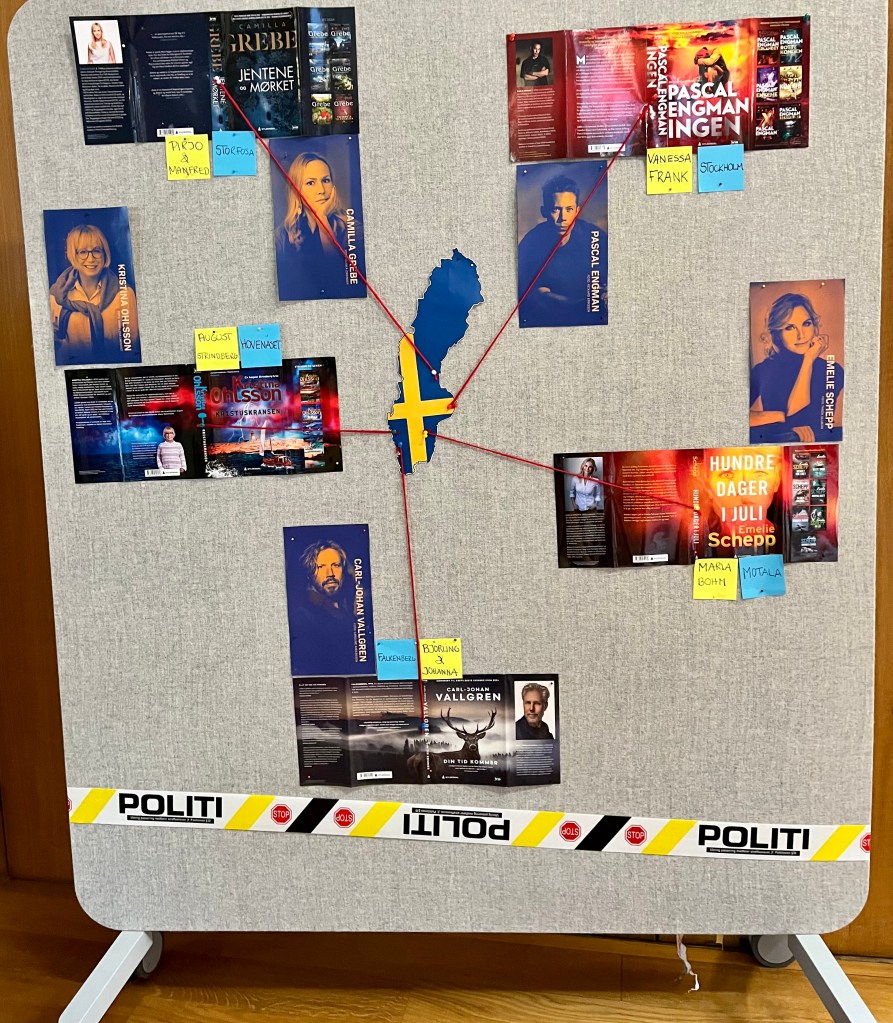

Nesbø was joined on stage by Sweden’s huge star Pascal Engman whose challenging but incredible Femicide / Råttkungen was the Winner of Petrona Award 2023 for the Best Scandinavian Crime Novel of the Year. Discussion in Norwegian and Swedish between masters of the thriller focused on function of the literature which of course includes the crime fiction. Its purpose, apart from entertaining and creating a fantastic reading experience, is the possibility to create some kind of meaning and understanding of the world and what is going on in the current climate, touching on the social, historical and political aspects. Both authors agree that it is also much better to finish a novel with an open ending rather than a happy ending because how would such a ‘happy’ conclusion to a terrifying story work out in practice really?

Gunnar Staalesen, called the Norwegian Raymond Chandler, also considers that writing and reading crime fiction can bring some kind of resolution, some sense of what’s happening around us. Staalesen was celebrating 50 years as a writer earlier in January this year. The short summary of his writing career, and relatively short chat on the stage with Nils Nordberg, another great writer and one of leading experts on crime fiction, don’t really show huge impact Staalesen has made on the readers, critics and other writers. I was lucky to read and review several of his books (We Shall Inherit The Wind, Where Roses Never Die, Wolves in the Dark, Big Sister, Wolves at the Door, Fallen Angels). He made his debut at the age of 22 with his first novel Uskyldstider / Times of Innocence in 1969. Since then, he has published a wide range of novels, plays and children’s books, but he is primarily known as a crime fiction writer. The books about a social worker turned private detective Varg Veum have been published in 23 countries, including France, England, Germany, Italy, Russia and Poland, and several of them have been adapted for cinema and television. The iconic Varg Veum is a truly exceptional complex character. And one of my all-time favourite heroes, too.

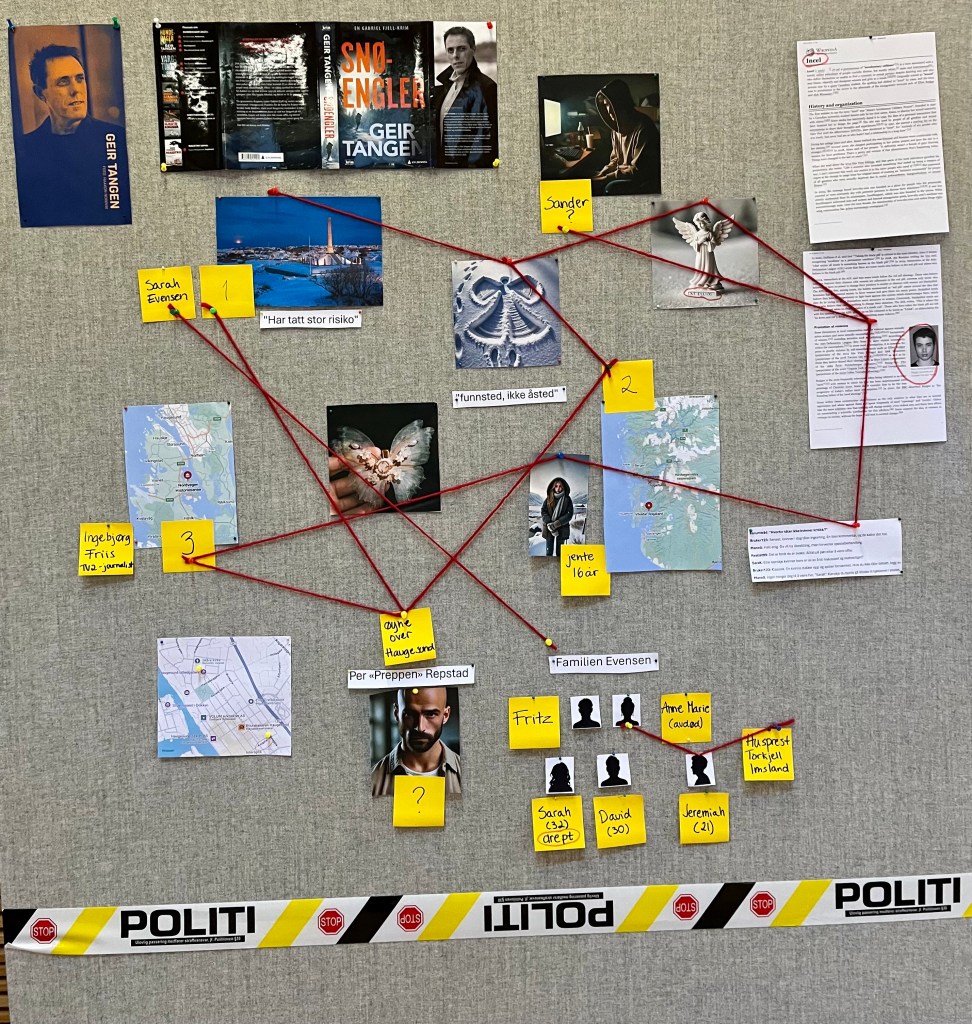

I spent several hours at Krimfestivalen, listened to the chats between Sarah Natasha Melbye and the Swedish mentalist and writer Henrik Fexeus, and later with immensely popular Elly Griffiths (UK) and Emelie Schepp (Sweden) about their fascinating and strong female characters: Ruth Galloway, Jana Berzelius and Maia Bohm. The powerful and often flawed fictional heroines are undoubtedly unforgettable. Helene Flood (The Therapist, The Lover), Torkil Damhaug (Medusa, Certain Signs That You Are Dead) and editor Marius Fossøy Mohaugen shared some of the intricacies of how to write a good authentic psychological thriller. The ‘who’ isn’t as important as ‘why’ to make people’s actions and motives believable.

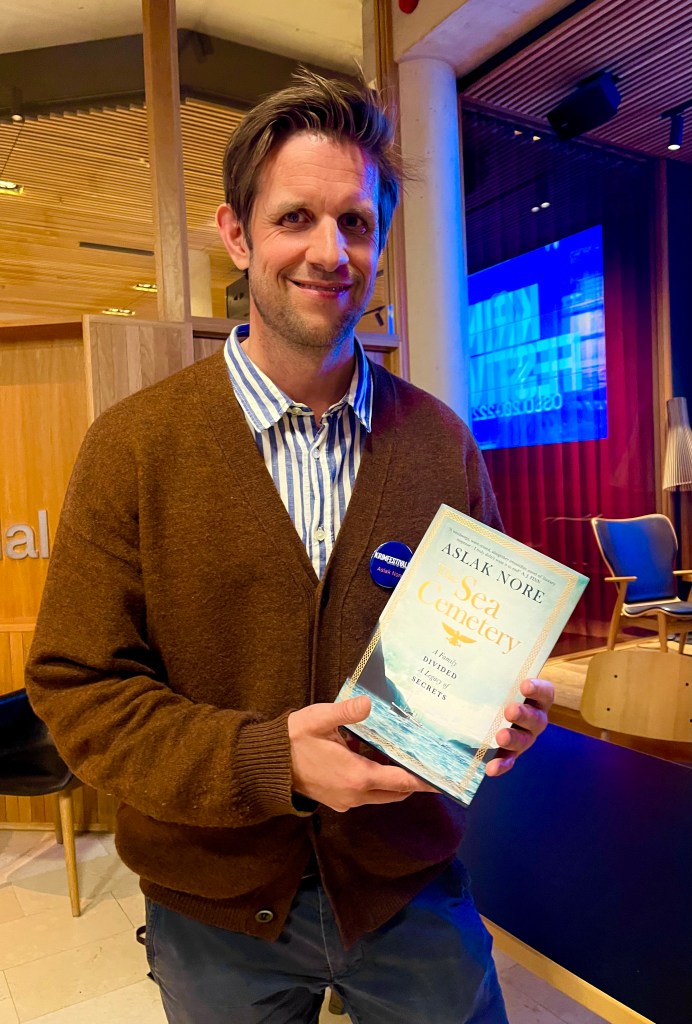

It was getting late when French Noir took over with the French author Bernard Minier and the French resident Aslak Nore in conversation. I enjoyed Night by Bernard Minier and am looking forward to reading Havets kirkegård / The Sea Cemetery by Aslak Nore.

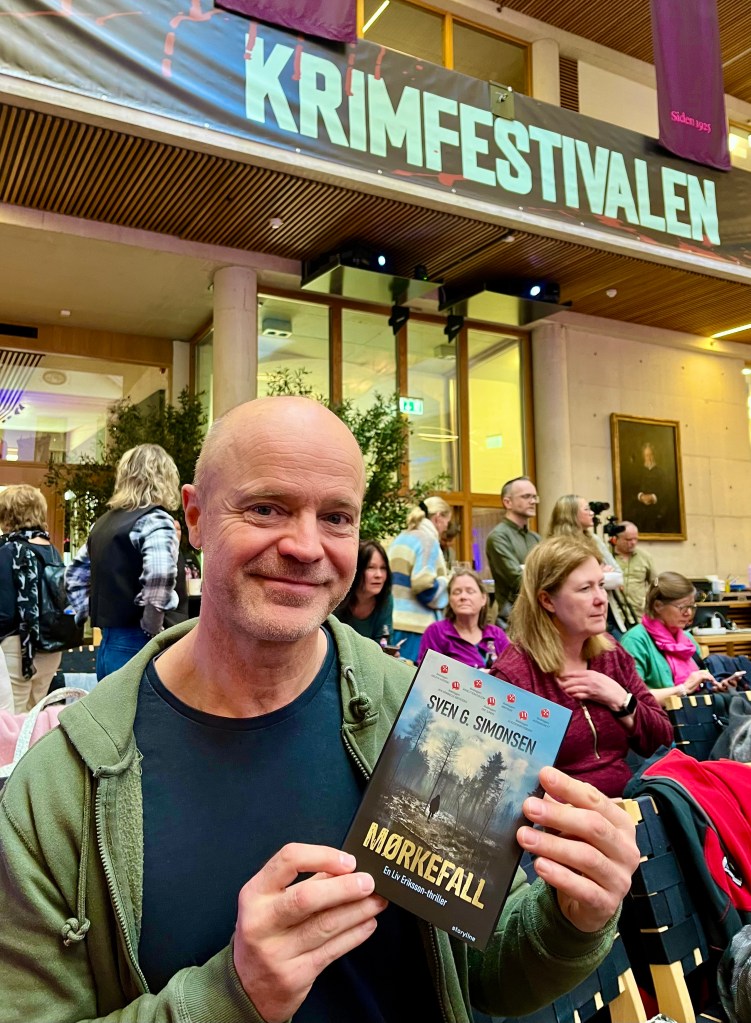

Only one day at the festival. Overwhelmed and tired in the best way possible, I felt that ‘my’ tribe is doing great. I got a new book: Mørkefall by Sven G. Simonsen, and had others signed. I didn’t miss my train home.

One of the exciting moments during the festival is the announcement of the nominees for the Riverton Prize / Golden Revolver 2024, to the author of the best Norwegian crime fiction work in the previous year:

- Du kan kalle meg Jan / You Can Call Me Jan by Anne Elvedal

- Fuglekongen / The King of Birds by Eva Fretheim

- Den ingen ser / The One No One Sees by Terje Bjøranger

- Tørt land / The Lake by Jørn Lier Horst

- Kongen av Os. Kongeriket 2 / Blood Ties. The Kingdom 2 by Jo Nesbø

This year’s prize will be awarded next month.