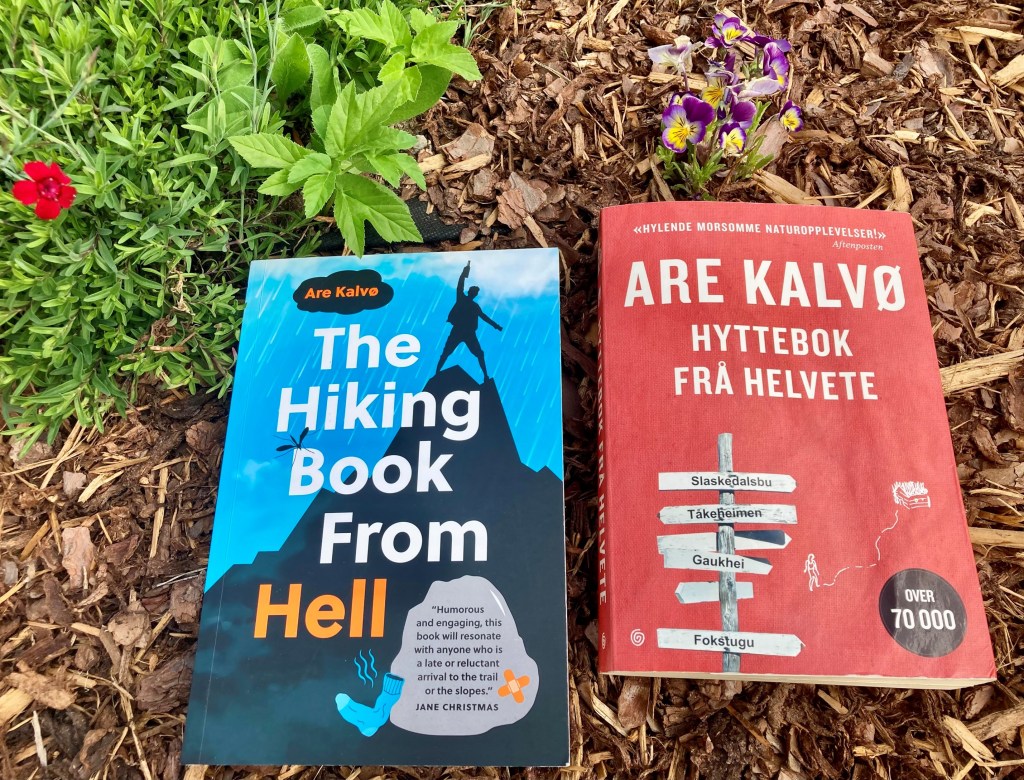

Sitting outside in the shade and reading The Hiking Book From Hell / Hyttebok frå helvete I am and feel really close to the nature. Seagulls screaming their heads off above me, mosquitoes having a huge hectic meeting around me. Dry grass, hot air, not a drop of rain; exhausted spiders. Not a mountain in sight but plenty of mountainous talk and thoughts in Are Kalvø’s love / hate (or is it indifference at first?) letter to the Norwegian nature which is here symbolised by hills, peaks, hiking, walking, reaching and admiring mountains. Are Kalvø, one of Norway’s leading comedians and satirists, has worked in standup for over twenty-five years. He has produced prize-winning musicals, reviews, an opera, and almost a dozen books. He often writes about things he doesn’t know much about. This is the first time that he is also writing about something he doesn’t understand. Even though he grew up in the picture-postcard perfect beauty of Western Norway he never became a true man of nature. He moved to the city, embraced the new urban life, and never looked back: ‘City folk go out into nature to find inner peace. Country folk go out into nature to shoot things.’

‘Sometime around his forties, Are Kalvø starts losing his friends… to the mountains. Friends who used to meet him at the pub are now hiking and skiing every weekend, and when they do show up, all they talk about is feeling at one with nature (without a hint of irony). When Are realizes he’s the only person who hasn’t posted a selfie on a mountain, he starts to wonder: does he have it all wrong? To find out, Are buys some ridiculously expensive gear and heads into the woods. The result of his sardonic trek is at once a smart and funny take-down of outdoors culture, and a reluctant surrender to nature’s undeniable pull. An adventure, a comedy, and a tragedy.’

Before I try to encourage you to read this book (not an example of crime fiction though death occurs in the hills, too), published by Gresytone in 2022, I must say that it seems as the translator Lucy Moffatt had much fun while working on it. The sentences flow, the words sparkle, the mood of bewilderment and curiosity is present on every page. Not to mention various nerd-type facts and opinions. I have heard the author in action, on TV only, and I bet your high quality be-all and end-all hiking boots and the latest ‘air transport’ jacket that his Norwegian voice and mannerisms are conveyed in English in the most authentic manner. I couldn’t stop laughing; questioned his comments, agreed with his reasoning, kept checking the map of Norway, and wondered where exactly he is going with his quest to understand the national hiking passion. A passion that represents one of the fundamental values in the Norwegian psyche. At first Kalvø doesn’t really care about outdoors: ‘There are three things in the world I really struggle to understand. Religion. Hard drugs. And outdoor life.’ He is not keen on carrying tons of trekking equipment and staying in rustic (obviously) uncomfortable cabins with weird names, then he decides to find out and explore the near-mythical feeling that apparently is then interpreted into loads of inspirational quotes and breathtaking photos on Instagram. He realises that yes, nature is indeed stunning and powerful. But you will have to dig into the experiences he describes, hour by hour, kilometer by kilometer, and which show the modern Norway in its most classic phase which has been developing in the last thirty to forty years.

I could quote whole witty and sensible passages. And I will… but not much. Just think about this Svalbard summary: ‘And let there be no doubt whatsoever about this: it was much more fun telling people about the dogsledding trip at the pub than it was actually being on the dogsledding trip. Snow I’ve seen before. Dogs too. And uncoordinated people in big quilted snowsuits. I live right next door to a kindergarten.’

Have you heard of Jotunheimen? The mountainous area of roughly 3,500 square kilometres in southern Norway is part of the long range known as the Scandinavian Mountains. Twenty-nine highest mountains in Norway are all located there, including the 2,469-metre tall mountain Galdhøpiggen. Jotunheimen is THE Holy Grail for the hikers and the nature lovers, and I want to go there, too. I already have super comfortable old hiking boots. This plan from Kalvø’s The Hiking Book from Hell will be useful to remember:

‘1st attempt to Jotunheimen in search of salvation. Purpose of the trip:

- Find inner peace

- Realize how small I am

- Experience something that’s difficult to explain

- Feel a desire to raise my arms to heaven

- Find out whether food and drink taste better, and whether views look better, if you’ve walked a long way

- Talk to, understand, maybe even like people I meet at cabins with peculiar names’