I was feeling quite nostalgic about the time when ScandiGang was in full swing. You might have never heard of it but for a group of us it was an amazing experience to be together in person and online and discuss all Scandinavian and Nordic things, go to various events, take photos, talk to big and small stars of the screen, eat cinnamon buns, and generally feed our hunger for NordicNoir. Most of it was possible to our patron saint Jon Sadler who at the time worked at Arrow Films, was instrumental in setting up Nordic Noir TV and its presence on Twitter and Facebook, and organised Nordicana, a hybrid film and literary festival in London. I was at first Nordicana in 2013, then in 2014 and 2015. After reading Jon’s recent post about his opportunity to build a successful brand that brought ideas, fun and frienships together, I looked through my old photos and comments, and found my old post about Nordicana #3.

So here’s it is, originally published on 12 June 2015 on Nordic Noir blog, run by my late friend, the irreplaceable wonderful Miriam V Owen. The blog is full of interesting articles by Miriam and her friends who shared her passion for NordicNoir in all its creative forms. It still available online and I would like to repost some of my earlier texts from my pre Nordic Lighthouse time.

‘ScandiBingo is my real passion, especially when it comes to books, films and TV shows. But when you also get food, drink, maps, mugs, T-shirts, design, culture and travel at the same place then playing the game is just amazing. And what better opportunity to shout ScandiBingo than at Nordicana which brought together all things Nordic Noir and beyond at the Art Deco Troxy in London on 6th and 7th June 2015. As the UK’s only festival of Scandinavian crime fiction the third Nordicana was an engaging, thrilling event and one that hopefully will be organised again.

So on Saturday, also the National Day of Sweden, I was there in search of ScandiBingo stars and heroes. Although tempting, it was impossible to be at two places at once. But ScandiGang friends immersed themselves in the rich programme of screenings, signings, informal chats and so throughout the day we swapped stories and smiles, soaked up the relaxed atmosphere and smell of Scandinavian cooking, and occasionally looked distinctly blue thanks to the lighting in the venue’s ‘mingling’ area.

Honest Cooking: The Simple Art of Scandinavian Food talk here, screening of a brand new French crime series Witnesses there… And a live theatrical performance, by the theatre group Foreign Affairs, of The Contract Killer, a Danish play by Benny Andersen (no, not of Abba’s fame).

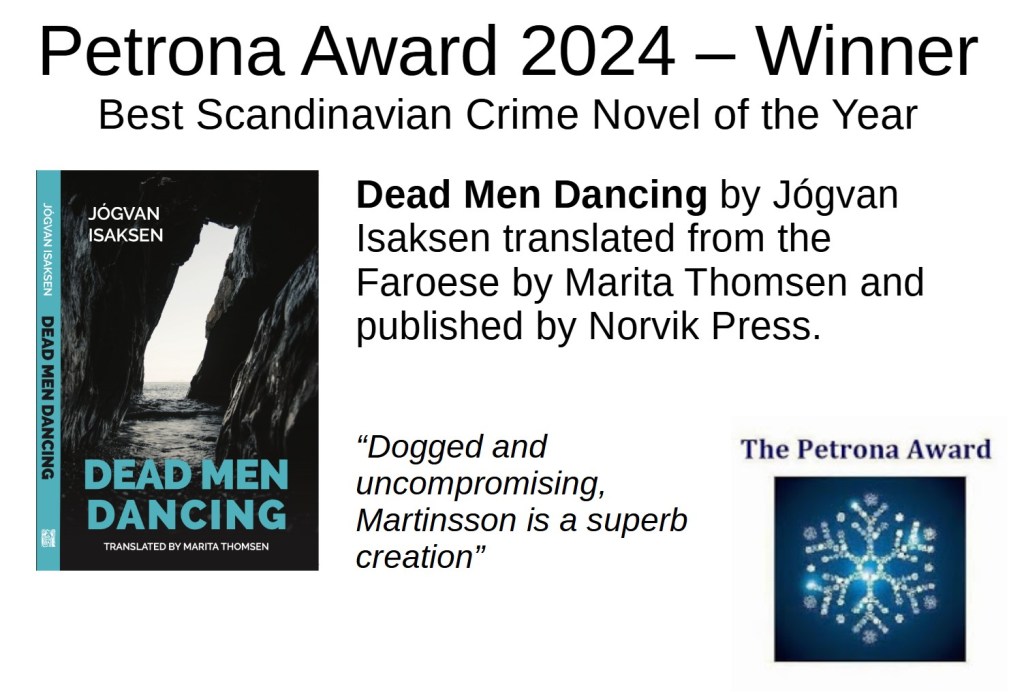

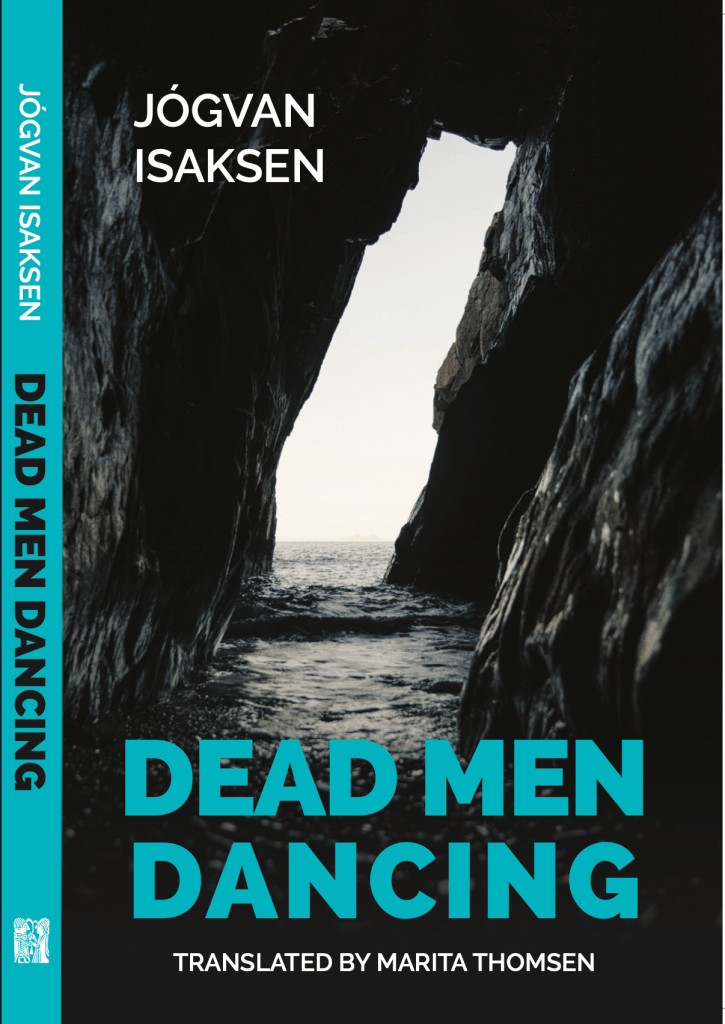

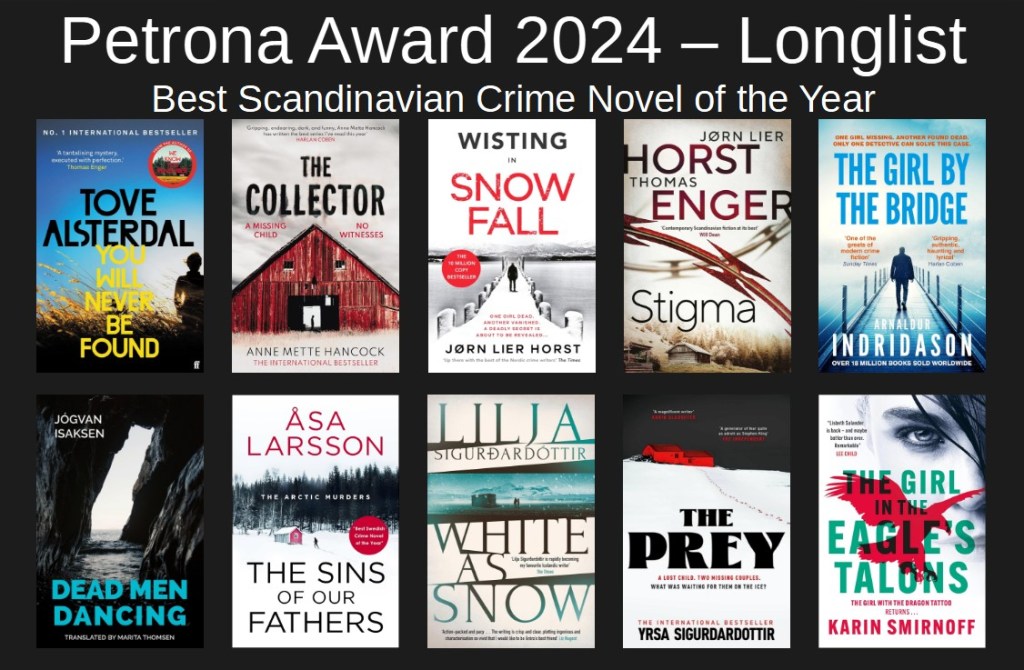

The literary start of the Nordicana was The Origins of Nordic Noir session, chaired by the omnipresent expert Barry Forshaw, who officially opened the event. Three panelists knew their subject inside out: Sarah Ward, author of In Bitter Chill, and one of The Petrona Award judges (for the Best Scandinavian Crime Novel of the Year), Quentin Bates, author of Frozen Out and further five books set in Iceland, and Jakob Stougaard-Nielsen of UCL Scandinavia Studies who is currently working on his book Scandinavian Crime Fiction. It’s definitely on my ‘To Read’ list. It was a fascinating discussion about the past, present and future of the Nordic Noir genre from different perspectives, experiences and backgrounds.

At the same time the main stage welcomed an exclusive premiere of the episode heralding the new season of the tense, brilliantly acted family drama The Legacy (Arvingerne), followed by a Q&A session with the cast members: Trine Dyrholm, Jesper Christensen and Marie Bach Hansen. Judging by the audience’s reaction after this session I’m certain that second season of The Legacy will be as complex and explosive as the first.

Beautiful and talented actress Sofia Helin, The Bridge star, interviewed by Angie Errigo, took us into the mind of the Swedish cop Saga Noren, a character who is so lonely in social situations, yet who cares about other people and doesn’t want to be lonely. Sofia missed Kim Bodnia who won’t reprise his role as Danish cop Martin Rohde but understood the change was a great thing for series three of The Bridge.

Sofie Gråbøl in conversation with bubbly Emma Kennedy, author of The Killing Handbook, showed how warm, friendly and utterly charming she is, and how different she is from her most famous creation, iconic Danish detective Sarah Lund. Sofie talked about the intense yet unbelievably enjoyable process of making The Killing (Forbrydelsen) and working with the scriptwriter and creator of the series Søren Sveistrup: ‘Writer is a God’. Asked whether there could be a fourth series Sofie replied that there is beauty in ending something that’s still good. She’s got the point, although I’d be happy to see her as Sarah Lund again. And again. Sofie also talked about the incredible chemistry when working with her friend Søren Malling on other projects as well (The Hour of The Lynx), and about giggling which sometimes turned the most heart breaking scene into a fit of laughter and connection: ‘When you giggle you have a certain connection with another actor. It’s akin to tickling emotion, embarrassment, and feeling’. The highlight of the conversation (and Nordicana!) was a sudden appearance of Søren Malling on stage when overjoyed Sofie couldn’t believe her eyes. And neither could we!

Danish ambassador Claus Grube introduced the screening of deeply moving series 1864. Watching the penultimate episode of shocking yet mesmerising historical drama on the big screen confirmed what we all knew: war is hell, politics seems a game to those who can afford to play, and the ordinary people find themselves helpless. Yet the acting, the drama, the emotions were so powerful! I was left feeling teary and speechless until excited Marian Keys appeared with the stars of the show: Danes Søren Malling, Sarah-Sofie Boussnina, Marie Tourrel Søderberg and Jens Sætter-Lassen, and a charismatic Norwegian Jakob Oftebro. The show contradicted the claim that there are only thirteen actors in Denmark (totally untrue!) and the ‘architects’ of these high quality shows tapped into the whole creative Scandinavian talent, regardless of borders. Discussion centred on Denmark’s response to the show and it demonstrated how differently history is seen through eyes of different generations.

Camilla Hammerich, author and Borgen producer discussed her work relating to Nordic Noir television and how she turned the intricately woven political series into a worldwide phenomenon. Camilla was overwhelmed by the fans’ interest, queueing for a quick chat and to have a copy of her book The Borgen Experience signed.

The screening of the first episode of the critically acclaimed Swedish mystery thriller Jordskott, and then Q&As with the leading actress Moa Gammell, creator/co-director Henrik Bjorn and producers Filip Hammarstrom and Johan Rudolphie generated quite a lot of interest from those in the audience.

I cannot wait for Nordicana 2016. In the meantime I’ll be following all Nordic Noir & Beyond stories…’

So this was ten years ago… 🙂